Befana's custom brings together a wide variety of intertwining traditions, Pagan and Christian, that overlap and affect each other.

January 6th - in Christian tradition - is the day of the Epiphany, also known as Three Kings' Day, the day of Jesus' physical manifestation to the three Magi who went to Bethlehem to see him. "Epiphaneia" in Greek means "manifestation" and the word "Befana" is nothing but a derivation of this word.

In ancient pre-Christian times, January was also an important month for celebrations: the ancient Romans celebrated the beginning of the year in god Janus (Januarius originates from this deity) and goddess Strenia's (the word “strenna”, gift, comes from this deity) honor. Additionally, since December and January were rather hard for agriculture, Emperor Aurelian proclaimed December 25th as “Sun's Day": henceforth an oak trunk had to burn continuously for 12 days (ie up to the "Twelfth Night" on January 6th) as omens for the following year would be drawn from its coal. During these twelve nights, goddess Diana, along with other female figures, was believed to fly in the sky over the fields making their soil more fertile and fruitful.

However, in Christian times, Diana and the flying women's pagan image was changed into the image of witches and evil - although, apparently, not erasing their original positive traits.

The Befana's custom of celebrating with bonfire, singing and dancing started already in thirteenth century; then, in sixteenth century, Befana was characterized by several witch figures and only later she became a single character encompassing, however, a strong duality (an old witch who brings gifts and also coal). Befana's roots in agricultural life are evidenced by her most characteristic gifts, nuts and oranges and the coal itself.

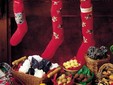

Nowadays, Befana - portrayed as an old lady riding a broomstick wearing a black shawl covered in soot as she enters children's houses through the chimney - visits all the children of Italy on the eve of the Feast of the Epiphany. She fills their stockings with candy and presents if they are good, or a lump of coal or dark candy if they are bad. The child's family typically leaves her a small glass of wine and a plate with a few morsels of food.

The above information is definitely not exhaustive in explaining all the traditions that converge into the Befana's custom. Suffice it to say that it is such an engrained and rooted Italian tradition that, throughout the many transformation and layers it wears, is still celebrated today, probably carrying way more meaning than we are aware of.